Last time, I explained at inordinate length that Bernard Suits thinks games have the following structure:

Well, the activity of playing a game has that structure. Your goal in playing (the large, outer target) is to achieve some goal inside the game (the smaller, inner target) by means of the methods and tools the game makes available to you.

The inner goal is usually something like, “crossing the finish line” or “getting the puck into the net.” The methods and tools the game provides, furthermore, are always mildly challenging. “Start 26.2 miles away and then run,” the game commands players. Or “put on skates and then use this weird stick to push the puck around these large Canadians who are trying to steal it.”

Photo by Taylor Friehl on Unsplash

How much challenge there is will vary. But there will always be at least one way of achieving the game’s internal goal that would be more efficient than the game allows. “No carrying the puck,” the rules of the game insist. “And no taking a cab to the finish line.”

But enough reminiscing! Consider what the game of baseball looks like from a Suitsian point of view. Theory is all fine and good, but if a theory doesn’t actually help us understand things better — if it doesn’t work — what’s the point?

Baseball’s “Prelusory” Goal

The basic, internal (“prelusory”) goal of baseball is to step on home plate.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Well, the goal of baseball is to touch home plate with some part of your body. It’s just usually easiest to do so by stepping on it. Home plate, after all, is way down there in the dirt. Look how far away it is. You don’t want to bend over. You’re old. Just step on it. That’s it. Just tap it with your toe, maybe.

More specifically, you want to touch home plate more times than the people on the other team do. That’s what Suits would call baseball’s “prelusory” goal — the goal that is “prior” to the game (the goal the game is built around). You don’t have to understand the rules of baseball to understand what it would mean to touch something more times than another person touches it.

But more importantly, you don’t have to know what makes something count as home plate (does it have to be a particular shape or be made of a particular substance or be in a particular spot), how the people touching it are supposed to touch it (with sticks? with their noses?), or how they are supposed to get themselves into position in order to touch it (by jumping from a great distance away? by crawling across the ground?), to understand the basic idea, “Your goal in this game is to touch home plate more often than those guys touch it.”

Unnecessary Obstacles

But that’s not all there is. If it were, every baseball team would hire a few tap dancers like Vera-Ellen and have them tap away.

But alas. For a home plate touch to count toward your team’s total, a number of conditions have to be met.

First, you have to step on (well, touch in some way) three “bases” before touching home plate will count.

Photo by Darrin Moore on Unsplash

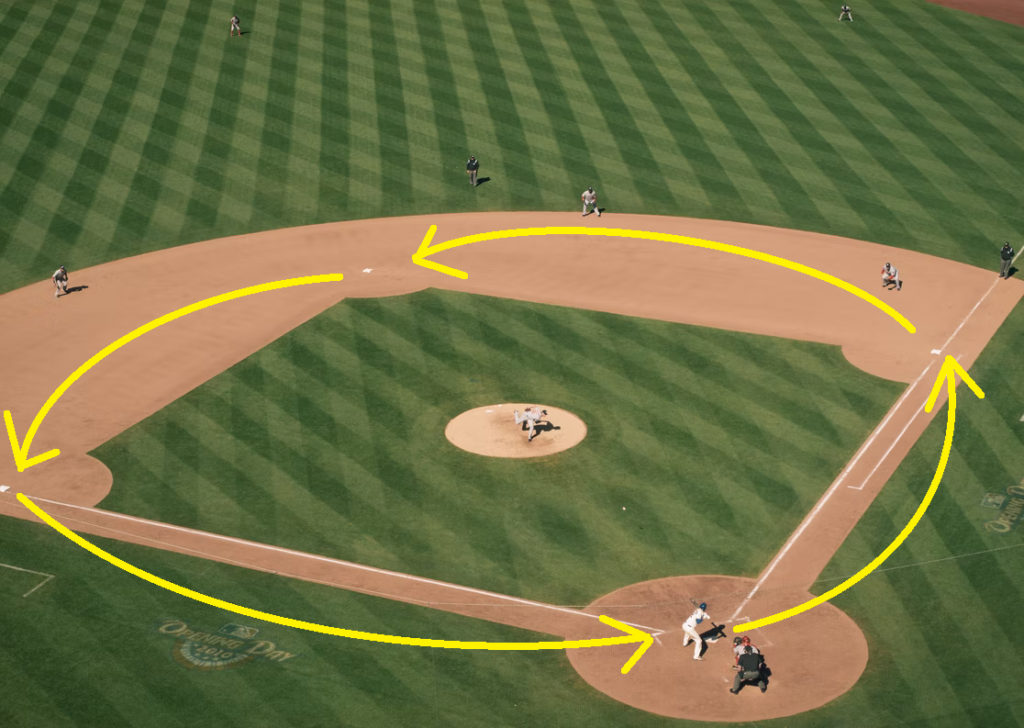

Second, you have to touch those three bases in a particular order. Fortunately, they have names that tell you the order you’re supposed to go in. And if you can’t remember their names, just remember that you’re supposed to go counter-clockwise.

And if you can’t remember that, just remember you’re supposed to go the opposite direction to the way the hands on a clock go.

And if you can’t remember that, it’s probably because you’re too young to have seen that kind of clock. It’s not your fault.

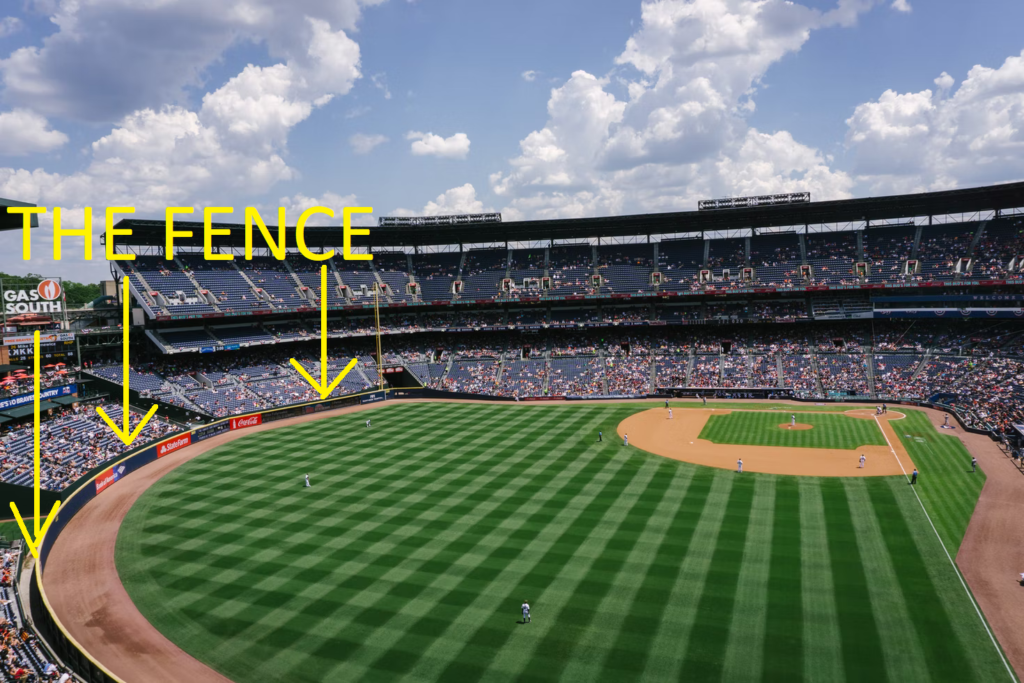

[But I added the beautiful arrows, so don’t blame Tomas]

If you don’t touch the bases in that order first, touching home plate won’t count.

Third, as you can tell from the image above, they put the bases super far away from both home plate and from each other.

If they put them closer together, it would be easier.

But no.

Fourth, they only let you touch home plate once per round trip. If you want touching home plate again to count, you have to first go back and touch the three bases (in the right order).

Fifth, before they will let you touch any of the bases, you have to hit a ball with a bat. That’s super difficult because hitting the ball doesn’t count unless it is first thrown by a member of the other team. And that person doesn’t want you to hit the ball. So, they’re going to throw it really, really fast. And you have to hit it while it’s still moving.

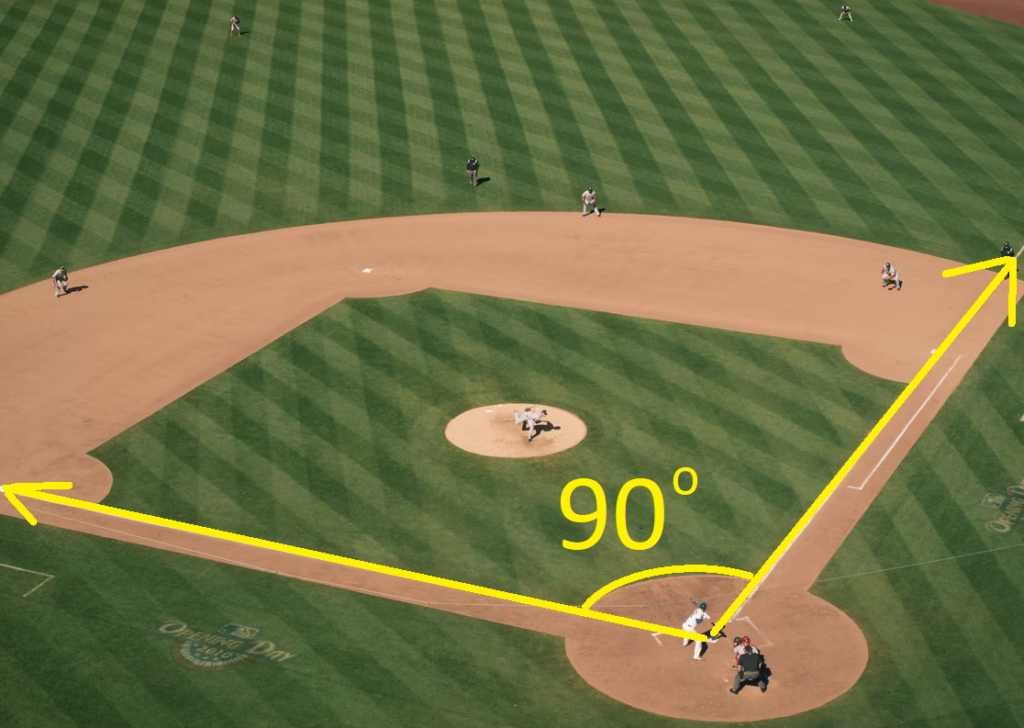

Sixth, even if you manage to hit the ball with the bat, it doesn’t count unless you hit it in a particular direction. There are 360 degrees in which you could hit the ball, but only a quarter of them count.

[But I added the beautiful annotations, once again, so don’t blame Tomas]

Seventh, if you try to hit the ball three times and miss, you have to give up your attempt to even reach the first base.

If you hit the ball but it doesn’t go in the right direction, this counts toward your three attempts (unless it’s the final attempt, in which case it’s a freebie).

And even if you don’t try to hit the ball, but your opponent threw it close enough for you to hit it, that counts as one of your three chances.

Eighth, if any of your opponents catch the ball after you hit it but before it hits the ground, you don’t get to go touch the three bases. Instead, you are “out” and have to let someone else have a go at batting.

Ninth, even if you hit the ball in the correct direction and the ball hits the ground before your opponents can catch it, your opponents can still keep you from touching the bases if they get the ball to the first base before you get there. And they’re allowed to throw it. So, you’d better run fast.

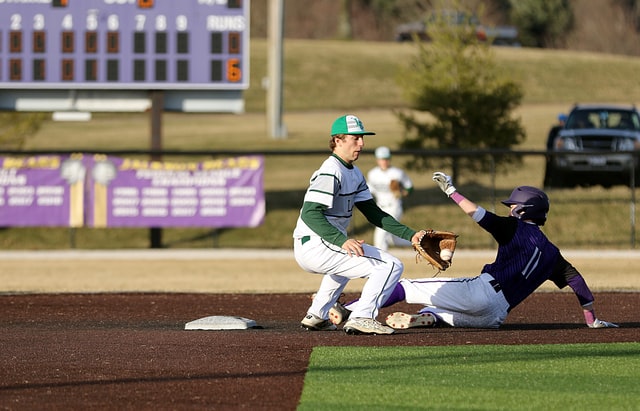

Tenth, even if you make it to the first base before your opponents can get the ball there, you still aren’t necessarily safe. If you aren’t currently touching one of the bases and one of your opponents touches you with the ball (either by holding it against you, or by holding it in their large “glove” and tapping you with the glove) you have to give up your attempt to reach home plate.

Eleventh, if you managed to make it to first base, another member of your team gets to take a turn trying to hit the ball. If they meet all the conditions described above for being allowed to run to first base, you must leave first base and run to second base. If you don’t, you will be ruled “out” and have to give up your attempt to reach home plate.

But then the whole drama you went through in trying to get to first base plays out again. If your opponents get the ball to second base before you can get there, you are “out,” and have to give up your attempt to reach home. If your opponents “tag” you with the ball while you are en route to second base, you are also “out.”

So, even when you have made it to safety, your own teammates’ attempts to reach home plate can put you back in danger.

A Brief Interlude

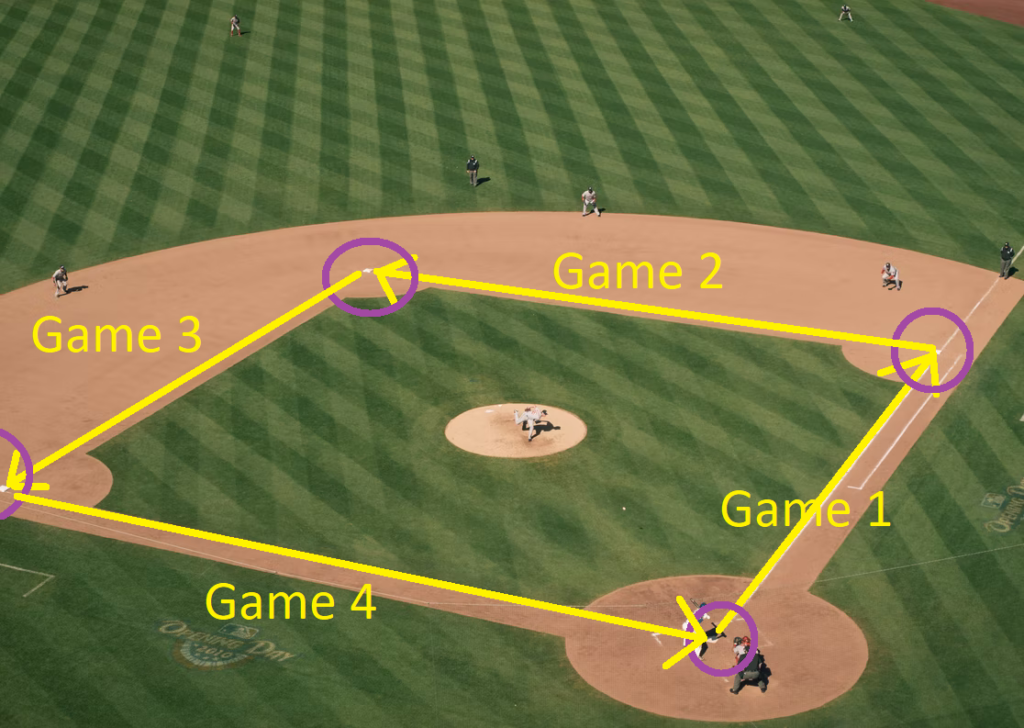

The dynamic we have just been discussing — needing to touch all three bases before touching home counts, the safety of being currently in contact with one of the three bases and the danger of being in between — turns the game of baseball into what we call “a series of mini-games” in video games.

Or, to use another term from video games, baseball has a clear “gameplay loop.”

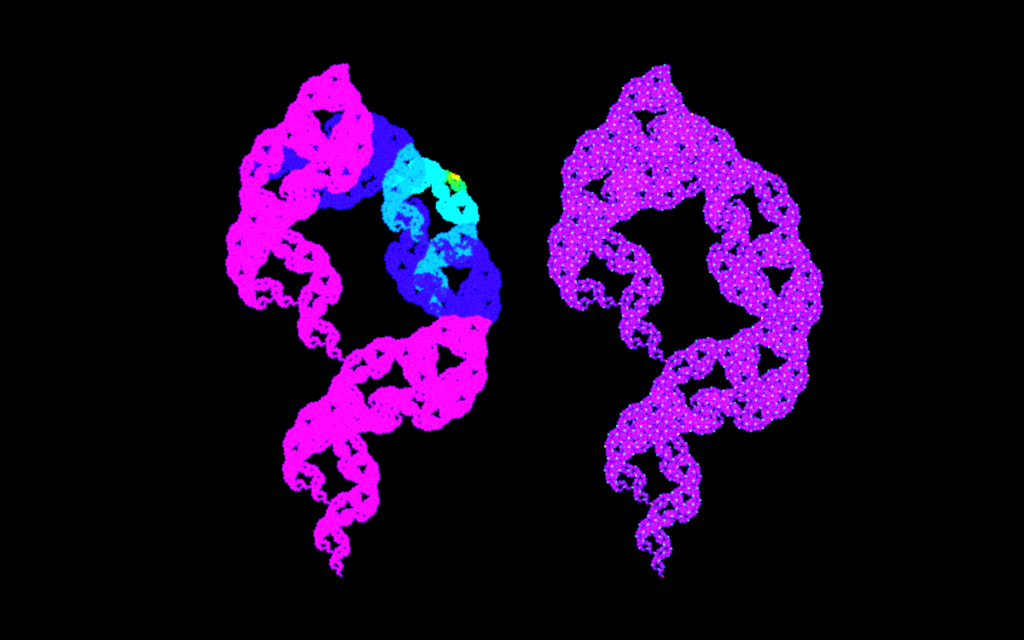

Or, to use a more mathematical idea, baseball has a quasi-fractal affair.

In effect, baseball has four prelusory goals — three that are intermediate and one that is final. And yet each is essentially the same as the others: you start from somewhere safe (e.g., home plate or first base) and have to get to somewhere safe (e.g., first base or second base) while your opponents are either trying to get a ball there first or trying to tag you with that ball first.

[But, yet again, I added the beautiful annotations, so don’t blame Tomas]

And once you get there, you have to do the whole thing again in order to get to the next base.

To put it another way, while actually winning requires you to make it all the way to home plate, making it to each of the three bases in term is a mini-win.

Back to the Obstacles

Twelfth, if anyone on your team is forced to give up their attempt to reach home plate in any of the above ways, this counts as an “out” for your team. If your team accrues three “outs,” they have to give up trying to reach home plate and instead let the other team have a turn at bat.

While it is the other team’s turn, it doesn’t matter how many times members of your team step on home plate. None of them count. If you want touching home plate to start counting again, you have to put “out” three of the other team’s members in one of the ways described above.

Thirteenth, you’re only allowed to trade turns with the other team nine times. If, after nine rounds (called “innings”) in which each team has had a chance “at bat,” the other team has managed to hit the ball and round the bases — reaching home plate legitimately — more times than your team, your team loses.

I could go on, but I think pointing out thirteen “unnecessary obstacles” is plenty.

Obstacles Summarized

Achieving the basic goal of baseball would be easier if any one of the thirteen rules above were changed. If there were only two bases, rather than three, or one rather than two, it would be easier to run the bases.

If you were allowed to hit the ball off of a stationary tee instead of having it hurled at you by an opponent, it would be easier to meet the conditions for running the bases.

Photo by Elisabeth Wales on Unsplash

Photo by Gene Gallin on Unsplash

If the other team weren’t allowed to simply get the ball to a base before you got there, but had to “tag” you with it, it would be a tad easier to make it from base to base safely. (This does happen in cases where a “runner” voluntarily leaves one base and heads for another. But whenever a runner is “forced” to leave one base for another, or to leave home for first base, simply getting there slower than the other team gets the ball there counts as failure.)

If you were allowed five chances to hit the ball, rather than only three, or were allowed to hit the ball in more directions than just the 90-degree wedge, or if the other team’s catching the ball before it hit the ground didn’t count as a failure on your part, reach home plate would be easier.

And so on and so on.

Furthermore, by approaching baseball from this Suitsian angle, the basic (fractal!) structure of the game becomes clearer. And we also see the way in which baseball sets things up so that players on the same team pursuing the same goal can actually get in each other’s way.

Enablers vs. Obstacles, and Obstacles as Enablers

The rules of baseball don’t just make players’ lives harder, however. By placing restrictions and requirements on one team, they make the other team’s task easier.

Photo by Jack Anstey on Unsplash

For example, while a batter only gets three chances to hit the ball, the member of the other team who is throwing the ball has to throw it (a) close enough to batter that it is hit-able, but (b) not too close. If they throw it too far away, or too close, four times, the batter gets to go to first base for free.

And if, heaven forbid, the opponent throwing the ball for the batter actually hits the batter with the ball, the batter also gets to go to first base for free.

Furthermore, if a batter can hit the ball far enough that it actually leaves the field before hitting the ground — going over the “fence” at the far end of the field — then the batter gets to run the three bases and return to home for free.

The Attraction of Balance

Suits argues that a game designer needs to set up the rules of their games so that players face neither too great a challenge nor too easy a task (see The Grasshopper, ch. 3).

This may put us in mind of Mihály Csíkszentmihályi‘s theory of flow, though Suits first pointed this out a couple years before Csíkszentmihályi introduced his theory. (In other words, I don’t think Suits had Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of flow in mind when he first described the way in which game designers need to tune game difficulty.)

Furthermore, Suits doesn’t think of players as primarily limited, disempowered, and restricted. Rather, he thinks that players find the challenges posed by games engaging, that they enjoy the activity of overcoming those challenges, and that games provide players with opportunities for exercising various abilities. (I have uploaded a scan of “The Elements of Sport,” in which Suits discusses this, since that essay is now long out of print.)

In other words, the way in which baseball is set up provides players with the chance to do things they would not normally be able to do.

Don’t believe me? How nice would it be if you could get people to go away by simply throwing a ball near them three times?

How nice would it be if you could get people to get out of your way — to stand back and simply let you achieve your goals — just by hitting a ball over a wall?

How nice would it be if you could achieve safety from all threats simply by standing in a particular spot?

Try baseball and find out!

My favorite articulation and exploration of this side of game playing is C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency as Art.

However, it is widely recognized on the psychological/sociological side of play studies as well. (In other words, it’s not just us philosophers who go on about this sort of thing,) See the work on “Self Determination Theory” by Andrew Przybylski, C. Scott Rigby, and Richard Ryan (e.g., “A Motivational Model of Video Game Engagement,” Review of General Psychology 14, no. 2 [2010]: 154–66).

Conclusion

Bernard Suits’s theory of game playing fits baseball remarkably well. Moreover, it illuminates aspects of the game that we might otherwise miss. In other words, it is both accurate and helpful.

But we’re not done. What I’m particularly interested in is whether we can analyze a game that is so clearly “Suitsian” from Kendall Walton’s point of view.

In so doing, I will be asking to what extent sports involves make-believe. And you can’t stop me.

Between this article, baseball, Suits, Csíkszentmihályi- it is interesting to think about how interconnected play, philosophy, psychology and sociology are.