𝅘𝅥𝅮 We Don’t Need No / Definitions 𝅘𝅥𝅮

Despite what Republican Senators might think, you can know what a word means without knowing its definition.

Don’t believe me? Try teaching a toddler a new word by way of its definition.

Go ahead. I dare you.

Photo by Stephen Andrews on Unsplash

“But I’m not a toddler,” says our impatient Senator. “I frequently learn what words mean by having my staff define them for me.”

Totally. Once you know enough words, you can start to learn new ones by combining old ones. But often — and to start — no definition is required.

What, for example, is the definition of “dog”? You can tell which animals below are dogs, and which aren’t. But can you list the set of properties all the dogs in this picture have, but the non-dogs lack?

Images from Unsplash contributors Alexander Andrews, Joshua Wilking, Mario Losereit, Alvan Nee, S J, Robina Weermeijer, Kanashi, Tanner Crockett, and Никита Теленков.

You can’t. And yet you just authored a bill banning all dog barking after 11pm, probably, as if you knew what you were talking about.

Old Dead White Guys

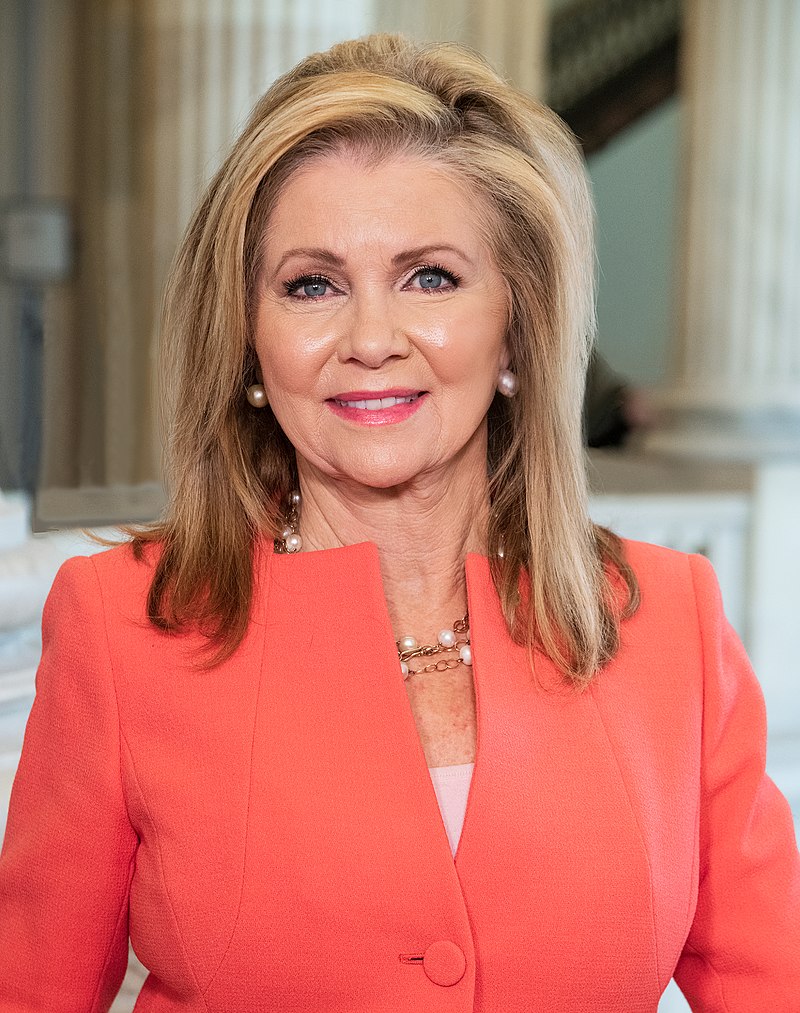

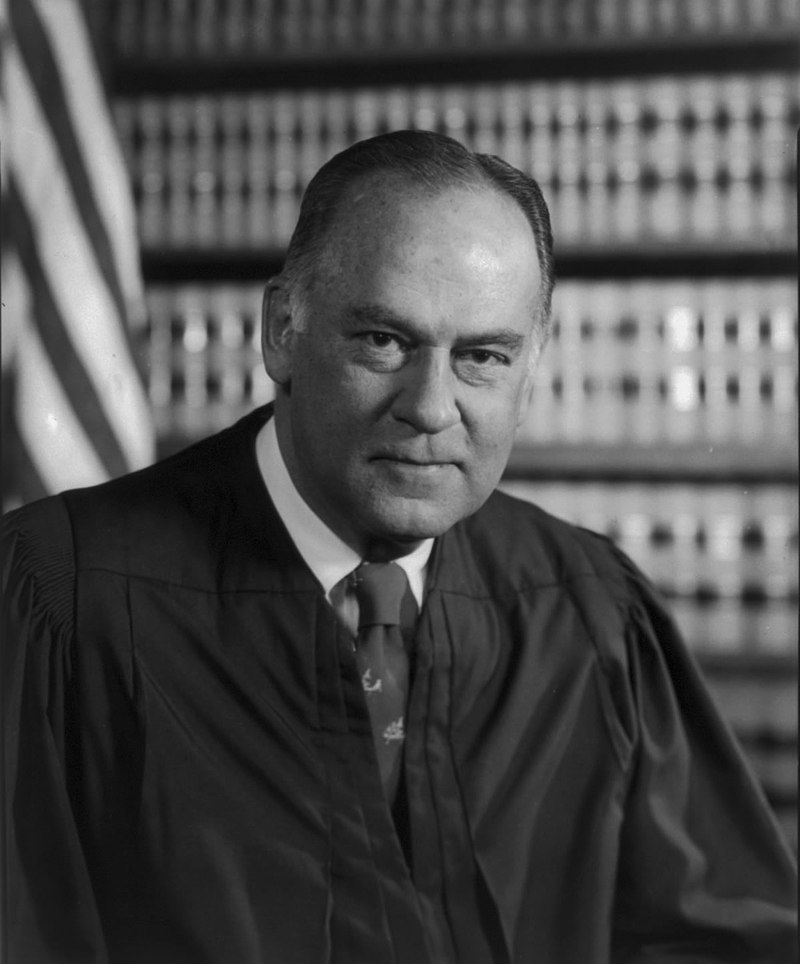

Approaching the same issue from a different angle, consider the famous words of Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart. He was nominated by Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower, so perhaps Republican Senators might listen to what he has to say.

What did he have to say?

Oh, you’ll know it when you hear it.

Not authoritative enough?

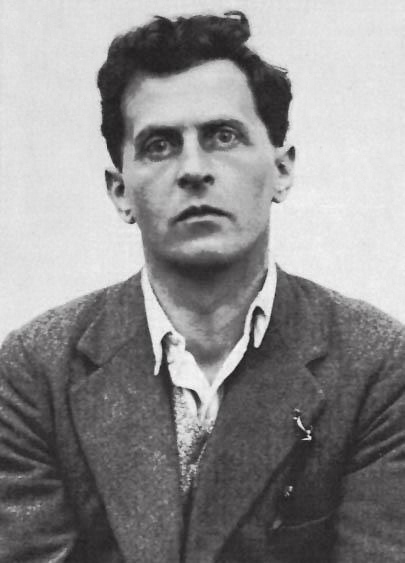

Well, try a philosopher on for size. Specifically, consider the work of Cambridge philosopher and logician, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

There is at least one word that everybody uses and yet nobody can define, said Wittgenstein. Maybe a biologist could come up with a definition for “dog” (though maybe not), but Wittgenstein argues nobody can define the word “game.”

Try to define “game,” why dontcha?

Everyone understands what games are. We know what people are talking about when they speak of “games.” And we can point to examples of games if we are trying to teach a child what the word means. We know that chess and soccer and poker and Super Mario Bros. are all games, and that yogurt, work, and going grocery shopping are not.

Photo of the game Concordia by Karthik Balakrishnan on Unsplash

But no one knows a precise definition of the word “game.” For any definition you come up with, you can think of things that don’t fit that definition and yet are still games.

So, we all know what the word “game” means even though none of us has a satisfactory definition of the word ready-to-hand, and none of us could find one even if we wanted to. That is Wittgenstein’s argument.

But a Definition of “Games” Would Be Handy Though

Wittgenstein is right. Well, he’s wrong about whether games can be defined, but he’s right about words in general.

The person who showed Wittgenstein is wrong about games is another philosopher, Bernard Suits. I think this is what he looked like:

The central photo is the only one I’m sure is of Suits. It’s from his philosophy department’s “In Memoriam” page!?! (left image source | right image source).

If you know anything about Suits, you’ve probably heard that the following is his definition of games:

[P]laying a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.

Bernard Suits, The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia (3rd ed., Broadview Press, 2014), p. 43

I first encountered that definition in Jane McGonigal’s 2011 book, Reality Is Broken, but it’s from Suits’s much earlier (1978) book called The Grasshopper.

Upon tracking down The Grasshopper, I saw that the quotation above was just a tiny piece of an enormous iceberg. Well, The Grasshopper isn’t a long book. It’s just packed full of great ideas and great writing and will change your life.

Your life, I tell you!

Unfortunately, if you only ever hear “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles,” you may end up missing out.

Suits calls that the “portable” version of his definition in The Grasshopper (chapter 3, p. 43). The first time Suits published that definition, however — in an obscure 1973 collection of essays — he called it “only approximately accurate” (Bernard Suits, “The Elements of Sport,” The Philosophy of Sport: A Collection of Original Essays, ed. Robert G. Osterhoudt [Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1973], 55). [Click here for a PDF scan]

So, we need to look at Suits’s full definition.

Suits’s Full Definition of Game Playing

Suits’s full definition of game playing is on the same page — in the prior sentence. But no one ever quotes it because . . . well, look at it:

To play a game is to attempt to achieve a specific state of affairs [prelusory goal], using only means permitted by rules [lusory means], where the rules prohibit use of more efficient in favour of less efficient means [constitutive rules], and where the rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity [lusory attitude].

Bernard Suits, The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia (3rd ed., Broadview Press, 2014), p. 43

“What in the heck does that mean?” you reasonably ask.

“I couldn’t even finish it,” you reasonably add.

And I equally-reasonably respond as follows.

Unpacking Suits’s Definition

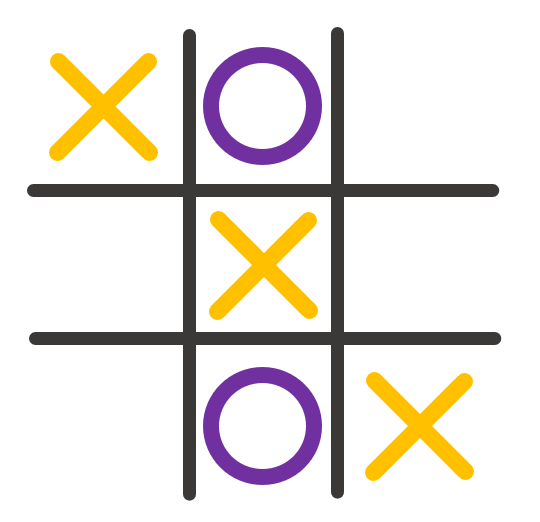

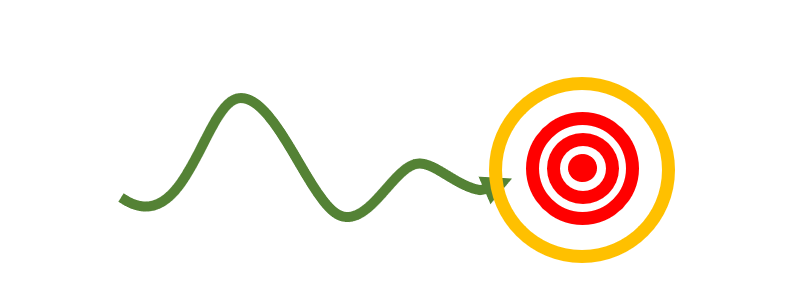

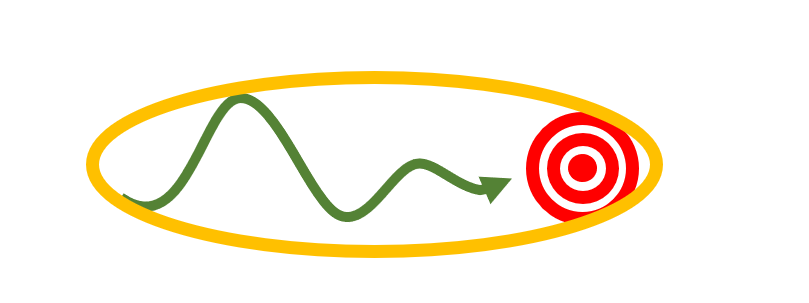

Here is a pictorial representation of Suits’s full definition of game playing:

The small white target in the center of the above image is what Suits calls the game’s “prelusory goal” (ch. 3, p. 38). It is usually something simple — and boring — like getting a ball into a net, or getting a ball across a line, or getting yourself across a line, or writing three Xs (or Os) in a line.

Photo by Ryan Reinoso on Unsplash

Why “prelusory”? Its prior (“pre-“) to the game (“-lusory”).

But what does that mean? Well, you can describe it without describing how the game wants you to achieve it. (See ch. 4 for details.)

In soccer (sorry, “association football”), there are a bunch of rules you have to follow as you try to get the ball into the net. But someone just learning about the sport can understand what it means for the ball to be in the net even if they haven’t yet learned that players aren’t allowed to use their hands to get the ball there.

Means and Methods

Once you understand the rules of a game, you realize that players aren’t just trying to achieve their game’s simple, boring (“prelusory”) goal. They are trying to achieve it in a particular way.

A tic-tac-toe player isn’t just trying to get three Xs in a row. Their full goal is something more like this: to-get-three-Xs-in-a-row-by-taking-turns-with-someone-who-is-trying-to-write-three-Os-in-a-row-in-the-same-spots-they-are-trying-to-draw-three-Xs.

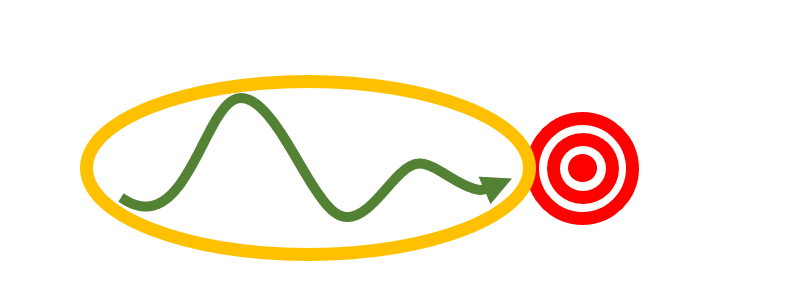

This more complex goal includes the game’s simpler, more boring (“prelusory”) goal. That’s why the diagram contains two targets (the larger of which contains the smaller).

This larger goal, furthermore, includes the way in which that simpler goal is to be achieved: using the tools and techniques that the rules allow.

Suits call’s the more complex goal the game’s “lusory” goal (ch. 3, pp. 38-39). But he also just calls it “winning” (p. 39). You can achieve the boring, simple goal of a game in many ways — that is why there are multiple arrows leading to the smaller target. But some of those ways will be cheating — that is why one of the arrows is X-ed out.

If you want to actually win the game — if that is your goal — then you have to get the ball into the net (or three Xs in a line) by following the rules.

Challenges

While a game’s “prelusory” goal is often simple, bland, and boring, a game’s “lusory” goal (winning; achieving-the-prelusory-goal-using-the-methods-allowed-by-the-game) is often quite interesting. But why?

Because it’s challenging. (See ch. 3, p. 34)

Sometimes the challenges imposed on players are themselves simple. In a foot race, you try to get to the finish line first. (That’s your “prelusory” goal.)

Photo by Ivan Lenin on Unsplash

But you aren’t allowed to start by standing on the finish line, or even by standing next to it. No. You have to start at least 100 meters away, and a lot can happen in 100 meters. What’s not allowed to happen, however, is tripping your opponents (ch. 3, p. 39), or hopping on a bicycle (ch. 5, p. 58).

“Getting to the finish line by starting far enough away that other people have a chance of getting there first, but trying to run faster than them so you get there first,” is the more interesting, more challenging “lusory” goal of foot races.

Upping the Complexity

With other games, however, the challenges are more involved. In basketball, you’re trying to get a ball through a hoop. That’s your “prelusory” goal. But they put the hoop several feet above your head and they turn it parallel to the ground. Then they tell you that throwing the ball upward through the hoop doesn’t count. You have to somehow get the ball above the hoop (which is already above you), and have it drop in from the top.

To make matters worse, they then put five other people in between you and the hoop, and give them the job of stopping you. You can’t just walk over to a conveniently-placed hoop and drop the ball in. You have to first overcome all the obstacles the game has put in your way.

Photo by desean robinson on Unsplash

Inefficiency

So, games not only have goals; they have structures (set-ups, “rules”) that limit the ways in which players are allowed to pursue their goals. And the ways in which players are allowed to pursue the game’s goals are usually challenging in some way.

Suits talks about the creation of challenge in terms of restrictions and limitations (e.g., ch. 3, p. 40). There tend to be multiple ways in which you could achieve any given goal. Some of those paths to the goal will be more efficient and others will be less. And, Suits argues, you will always find the most efficient path in the group of forbidden paths. Players are restricted to inefficient means.

It would be more efficient to cross the finish line, for example, if you could start closer. It would be more efficient to get the ball through the hoop if you could do so on a court not filled with opponents. It would be more efficient to write three Xs in a row if you didn’t have to take turns with another player who writes Os in all the places you wanted to write Xs.

Or, to use a different sort of example, it would be much more efficient for Mario to get to the flagpole if he could start right next to it. And even if he couldn’t start right next to it, it would be more efficient to get there if there weren’t massive holes in the ground, giant green pipes, and dangerous enemies he had to jump over. And even if those things were there, it would be more efficient if there just wasn’t gravity and he could fly over them all.

(How is this site allowed to exist?)

So, in setting up their games to be interesting, game designers usually try to create challenges. But whether or not you find their creations challenging, you will always find that they require you to act inefficiently.

The Playful (“Lusory”) Attitude

A game designer can’t make their game too inefficient or pursuing the game’s goal will change from being an interesting challenge to being a frustrating chore. But the right kind of inefficiency will actually attract players (ch. 3, p. 32-33).

Why? We accept inefficiency if it is necessary for safety, or if it is required in order to act morally, Suits points out. But if it is neither of those, we call the inefficiency “bureaucratic red tape” and decry it to the heavens (ch. 3, pp. 33, 40-41).

Except in games.

The Journey, the Destination, or Both

There are three things that we might value in any goal-directed activity.

(1) The most obvious is the goal of that activity, considered separately from whatever means are used to achieve it. For example, someone might dislike writing, but like books so much that they will put up with writing in order to get a finished book. For them, it’s the destination, not the journey.

(2) The second is the means or methods for achieving that goal, considered independent of the goal toward which they aim. For example, a person might have to drive to some meeting they would rather avoid, and yet enjoy driving their fancy sports car to get there. For them, it’s the journey, not the destination.

(3) The third thing we might value in any activity is the whole thing: pursuing-some-goal-by-way-of-some-means. Instead of valuing the goal independent of (and perhaps even as opposed to) the means, and instead of valuing the means independent of (and perhaps even as opposed to) the goal, you might value the particular process of pursuing a particular goal. While valuing the journey and destinations for themselves, you might also enjoy the journey because of where it gets you and the destination because of how you got there.

Holistic Gaming

Suits insists that you will never understanding why players play games if you see games as activities primarily focused on their purported goals (ch. 3, p. 41). So, option (1) is out. But that still leaves options 2 and 3.

C. Thi Nguyen has argued convincingly — to me, at least — that you need to genuinely value the goal you are pursuing in the sort of game playing Suits describes. You don’t have to value getting the ball across the line or into a hole outside the game; but for the duration of the game, you need to care a lot about ball locations.

As independent confirmation, consider playing golf. More specifically, consider a person who just loves hitting golf balls with golf clubs. For them, clubs and balls are toys. They don’t particularly care where the balls end up; they just enjoy the experience of swinging the club, feeling and hearing the club connect with the ball, and watching the ball go zooming off into the distance

That activity would count as playing around with golf stuff, but not playing playing a round of golf. Right? RIGHT?

In contrast, consider someone who enjoys actually playing the game of golf. They’re probably a Republican Senator, or the type of person who hangs out with Republican Senators.

Photo by Sugar Golf on Unsplash

But let’s ignore that, for the moment. Instead, ask yourself whether they would be as happy spending their Saturdays whacking golf balls in any old direction as they are whacking golf balls in the direction of holes in the ground.

I think the fact that people play rounds of golf (rather than “just playing around” with golf equipment) is evidence that golf’s particular goal is key to what golfers value. Surely the clubs and balls are toys for them, just as much as they are for someone who is merely playing around. And surely they enjoy hitting golf balls with golf clubs as an experience just as much as someone who is just playing around.

However, a golfer must value even more the hitting of golf balls with golf clubs in an attempt to sink those balls into holes. That is, golfers must value both the whacking and the sinking, the whacking as a means to the sinking, and the sinking because it is achieved by the whacking. (Compare Suits’s discussions of golf: ch. 3, pp. 25, 26, 28, 32, 35, etc.)

Photo by Robert Ruggiero on Unsplash

𝅘𝅥𝅮 All Together Now (All Together Now!) 𝅘𝅥𝅮

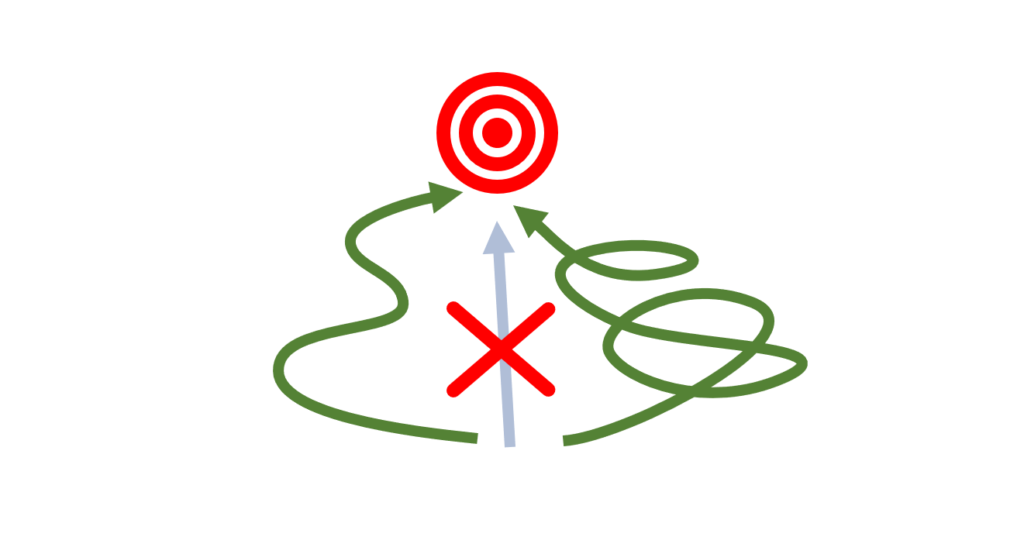

So, here once again is Suits’s definition of game playing, but as an image:

This, being interpreted, is as follows:

- Small target:

the basic “prelusory” goal of the game (e.g., getting a ball into a net) - Arrows:

ways of achieving that “prelusory” goal (e.g., kicking the ball without ever using your hands; carrying it and throwing it with your hands; cutting the net and sneaking it in by hand when nobody’s looking; firing it from a cannon; starting the game with the ball already in the net) - Curved or winding arrows:

inefficient ways of achieving the “prelusory” goal (e.g., kicking without using your hands) - Straight, but X-ed out arrow:

a more efficient — but disallowed — way of achieving the “prelusory” goal (e.g., carrying it by hand) - Large target:

the player’s “lusory” goal (to achieve the prelusory goal in the ways allowed)

In this image, note that the outer target presents the entire activity (the means/methods/paths and their goal) as being together what the player is aiming at. They combine to make up the bull’s eye.

Furthermore, whether there is anything beyond the general goal of engaging in that activity (e.g., the additional goal of gaining prize money or prestige by winning) is left out of the diagram. This is my attempt to represent Suits’s claim that in playing a game, we accept the rules of the game at least because we are aiming to participate in the activity of playing the game and those rules define that activity. (See ch. 13.)

To decide how well or poorly this theory of games works, it would be good to try to analyze a few games from its point of view. But this post is already too long. So, maybe next time.

So would writing a poem be a “game” according to this definition? I’m thinking of xkcd 1045 in relation to this.

Oh, good point. I think so. (That XKCD is a great illustration!) Given the importance to creativity of working within restrictions — and how much artists (often) really enjoy that process — I think many (most? all?) creative activities are games. Or at least the two activities are species of a common genus.

One difference between doing art and “paradigmatic” games is that creative activity often produces a lasting result that is valued in itself even after the activity has reached its conclusion. (In contrast, nobody cares where the soccer ball is after the game is over. The artistic work of Andy Goldsworthy and the creation of sand mandalas may be more like traditional games.) But that may just mean that creative work is — ironically — often something like professional sports, where players both enjoy playing the game and are seeking to “build a career” thereby.

[…] time, I explained at inordinate length that Bernard Suits thinks games have the following […]